TORONTO – A team of French and Canadian scientists have identified preserved embryos within the eggs of a tiny shrimp-like creature believed to have lived over 500 million years ago, raising questions about both the development of the creatures’ brooding abilities and the likelihood of such delicate materials surviving for thousands of millennia.

Waptia fieldensis is a tiny, shrimp-like arthropod whose fossilized remains were first found 100 years ago in Cambrian layers of fossils in Canada. Now extinct, Waptia was a frail creature that carried the eggs of its young within its own body.

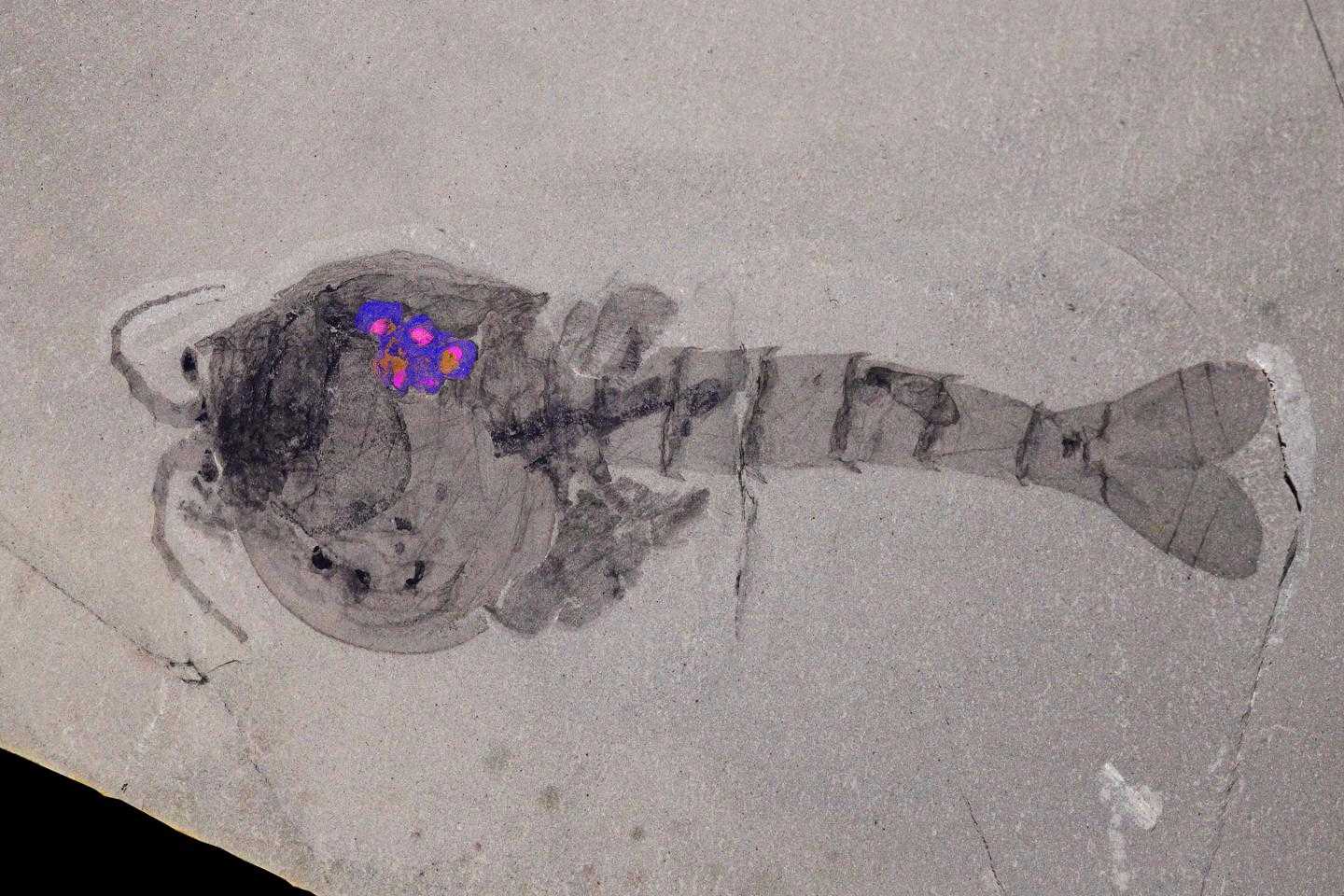

Canadian researchers studying Waptia specimens recently made a startling discovery: despite the fossils’ purported ages, collections of tiny eggs somehow survived within their fossilized bodies. The scientists marveled at the remarkable condition of the creatures, describing them as “exceptionally preserved.”

“New, exceptionally preserved specimens of the weakly sclerotized arthropod Waptia fieldensis from the middle Cambrian (ca. 508 million years ago) Burgess Shale, Canada, provide the oldest example of in situ eggs with preserved embryos in the fossil record,” the researchers wrote in a report published earlier this month in the journal “Current Biology.”

A December 17 press release from the University of Toronto heralded the discovery as the “oldest evidence of brood care in the fossil record.”

“Clusters of egg-shaped objects are evident in five of the many specimens we observed, all located on the underside of the carapace and alongside the anterior third of the body,” Jean-Bernard Caron, a University of Toronto professor who co-authored the study, said in the release.

Though the Waptia fossils were first unearthed over 100 years ago, it wasn’t until scientists recently revisited the specimens when the eggs and embryos were noticed.

The researchers attempted to tie their discovery into the evolutionary framework, proposing that their discovery is evidence of “rapid evolution of a variety of modern-type life-history traits”—namely, care for offspring by egg-bearing females.

However, others interpret the discovery as yet another instance of evolutionists struggling to explain the sudden appearance of complex physiology and advanced behavior among allegedly “simple” organisms.

“Waptia is a ‘shrimp-like arthropod’ with a lot more body complexity than the ability to lay eggs and hold them under its carapace,” an article last week on “Evolution News and Views” reports. “It had a nervous system, sensory organs, stalked eyes, antennae, respiration, digestion, and the ability to swim. Nevertheless, the ability to lay eggs and transport them to a protective place constitutes an additional design in this animal, requiring genetics and behavioral preparedness.”

“It’s amusing to see the euphemisms evolutionists use for the Cambrian explosion,” the article continues. “The paper spoke of the ‘Cambrian emergence of animals.’ The news release calls the Cambrian explosion ‘a period of rapid evolutionary development when most major animal groups appear in the fossil record.’ Why call it evolutionary development? If animal groups just ‘emerged’ or ‘appeared’ in the record, that’s not evolutionary.”

Another debatable aspect of this recent discovery is the likelihood of eggs and embryos surviving hundreds of millions of years. As previously reported, the discoveries of a variety of perishable biomaterials—including dinosaur blood cells and proteins within ancient shells—create predicaments for evolutionists, who maintain that such materials are tens of millions years old.

Become a Christian News Network Supporter...