(Morning Star News) – A case involving the constitutional position of sharia (Islamic law) courts in the Malaysian legal system could strengthen the power of the courts to block Malay conversions from Islam.

(Morning Star News) – A case involving the constitutional position of sharia (Islamic law) courts in the Malaysian legal system could strengthen the power of the courts to block Malay conversions from Islam.

In the potentially landmark case, due to be heard on Thursday (Aug. 13), the Federal Territory Islamic Council claims that sharia courts are separate from and not subject to Malaysia’s federal court system.

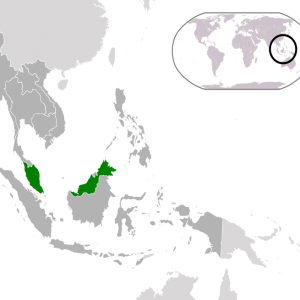

Malaysia has two legal systems: the sharia courts and the federal courts. The sharia courts settle family matters (such as divorces), inheritance questions and violations of the pillars of Islam. These courts can impose limited punishments (six months’ imprisonment and fines up to about $1,300). They apply exclusively to Muslims – only Muslims can bring cases to these courts, and until 2006 only Muslims testified in them.

A Christian lawyer, Victoria Martin, noticed that it was difficult to resolve interfaith disputes in sharia courts, so she obtained a diploma in sharia from the International Islamic University Malaysia. In August 2009, she applied to the Federal Territory Islamic Council (Majilis Agama Islam Wilayah Persekutuan, or MAIWP) for permission to practice in sharia court.

Her application was not processed because she was not a Muslim; rule 10 of the Sharia Court Rules Act (1993) states that sharia lawyers must be Muslims. By contrast, Singapore, which has a similar legal heritage, allows non-Muslims to practice in sharia courts.

In October 2009, Martin sued in Malaysian court requesting a judicial review of the rejection of her application. She lost, but later she won on appeal. The appeals court cited section 59(1) of the Sharia Court Rules Act (1993), which states that anyone with “sufficient knowledge of Islamic law” may be an advocate (attorney) in sharia courts.

Both the Malaysian Attorney General and the MAIWP have challenged Martin’s argument that her constitutional rights have been denied. Their case is going to be heard in the Malaysian Federal Court on Aug. 13, pitting constitutional rights against sharia.

The Islamic Council holds that because Islamic law always prioritizes the rights of the community over those of an individual, such laws should not be subject to freedoms that are part of the Malaysian Federal Constitution.

A decision for Martin would affirm the supremacy of the Federal Constitution. A decision against her, however, would mean that Islamic laws supersede federal laws. This would place the sharia courts beyond the reach of the federal courts.

If the position of the sharia courts is beyond review of federal courts, Malaysia’s 15 million ethnic Malays would be affected immediately, because all Malays are defined in the Constitution (Article 160) as Muslims. As “sons of the soil” (bumiputeras), they are given special affirmative action types of privileges.

One consequence of bumiputera status is that it is not possible for a Malay to convert to any other religion without changing ethnic status. Only sharia courts can change a person’s religious (and ethnic) status. A decision against Martin in the case thus would strengthen the sharia courts’ power to impede Malays converting to other faiths.

In short, the Martin case will be critical in defining the position of the sharia courts with respect to the federal court system. The placement of one system over the other will rest on the decision.

Become a Christian News Network Supporter...