(Morning Star News) – Intelligence officials in Cuba have increased harassment of an independent journalist, summoning the Christian and his mother twice in the past two weeks to threaten harsh consequences if he continues reporting on human rights issues, sources said.

(Morning Star News) – Intelligence officials in Cuba have increased harassment of an independent journalist, summoning the Christian and his mother twice in the past two weeks to threaten harsh consequences if he continues reporting on human rights issues, sources said.

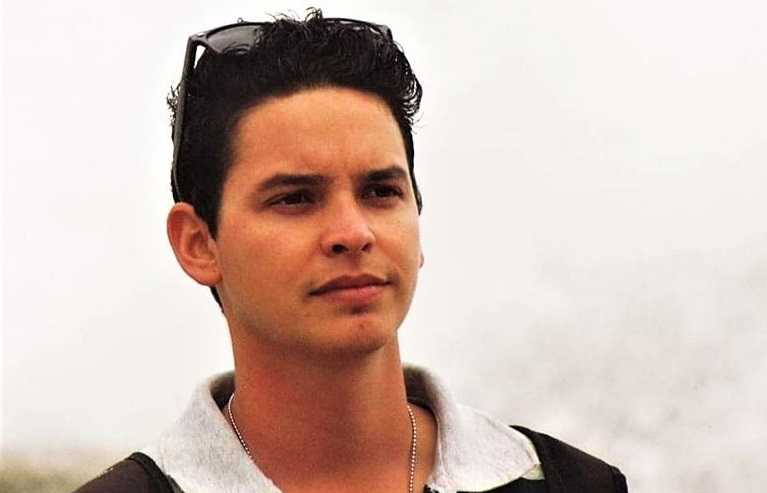

As part of his Christian calling, Yoe Suárez has reported for non-state media outlets in Cuba since 2014 about human rights and freedom of religion issues, including the imprisonment of husband-and-wife pastoral team Ramón Rigal and Adya Expósito. They were imprisoned in April 2019 for homeschooling their children.

Following a series of interrogations and threats by Cuba’s Department of State Security (DSE, the inland intelligence branch) over the past year, an intelligence official identifying himself as a second-in-command-for-the-press summoned Suárez and his mother on April 3 to the Siboney Police Station, Playa municipality in Havana, according to Suárez.

The official, who identified himself as “Captain Jorge,” issued a series of implied threats to Suárez’s mother about consequences her 29-year-old son would suffer if he continued working as a reporter outside of Cuban intelligence controls, Suárez said.

“He told us, ‘You don´t know what a dungeon is, or what it is to have a patrol in front of your house,’” Suárez told Morning Star News.

Suárez added that the official said, “The Office of the Prosecutor and Minors can intervene,” suggesting they could take him into custody and also take custody of Suárez’s less than 2-year-old son. Cuban civil law’s Family Code states that “both parents, or one of them, will lose custody over their children when they are convicted as a sanction for a final sentence issued in criminal proceedings.”

“This time they were much less kind than the last,” Suárez told Morning Star News. “He mentioned to me an article of the penal code under which I qualified for the crime of mercenarism.”

Cuba’s mercenarism law (Law 62, Section Eight, Article 191, Subsection 1 of the Cuban Penal Code) calls for prison of 10 to 20 years, or death, for a Cuban citizen who, “in order to obtain payment of a salary or other type of material retribution, is incorporated into military formations fully or partially integrated by individuals who are not citizens of the State in whose territory they intend to act.”

Subsection 2, Article 191 provides similar penalties for anyone “who collaborates or executes any other act aimed directly or indirectly at achieving the objective indicated in the previous section.” Cuban intelligence has a historical precedent of accusing Christians of being CIA agents on pretexts ranging from receiving a Christmas card from abroad to receiving offerings from Christians in foreign currency.

The official told him that he shouldn’t underestimate the DSE, Suárez said. Adding another level of pressure, “he told me that he had many contacts, and that through them he could spread the word that I was a State Security agent, to discredit me,” Suárez said.

“After that, and in front of my mother, he had no qualms about asking me if I wanted to join DSE as an informant, apparently within [Cuban newspaper] Diario de Cuba,” Suárez said. “I told him that my work is strictly journalistic, that I do not do police or intelligence work. Then he says to me, ‘Well, I’m not a police officer, and this is not a recruitment because that takes longer; State Security does not jump into a pool from a fifth floor without first measuring the depth, width and temperature of the water.’”

Suárez said the official told him he does not care if a journalist works for a non-state media outlet “as long as he does so under the control of the State Intelligence.’”

When Suárez declined to promise that he would work under intelligence controls, the officer said he had power to make him look like a government agent, causing him to lose credibility as a journalist and in his personal life, Suárez said. He warned the journalist that this would be the first and last time he would talk with him, and that the next time they saw each other would be in an “operation” against Suárez.

The April 3 encounter took place a day after two DSE agents summoned Suárez’s mother to a travel agency office near her home to interrogate her.

“All they seek is to put pressure on me through my family,” Suárez told Morning Star News. “My mother is very disturbed – fearful for me and for the consequences I may suffer. Right now, she is not able to even speak.”

The previous week, on March 27, two government agents summoned Suárez to Siboney Police Station and, while interrogating him, said they could “save” him from intelligence punishment – that he still had time to correct his ideological course. They asserted that the “dialogues” of recent interrogations represented a first phase, but that other, harsher phases would come if he continued to report for Diario de Cuba and other “enemy” media outlets.

Reporting on Rights Issues

Suárez, a member of the Cuban Evangelical League, said authorities are targeting him not for anything specific but due to “a cluster of anger about my work.”

The anger stems from the visibility his reporting has given to cases sensitive for the communist regime, he said. Along with the pastoral couple’s imprisonment for homeschooling, such cases include evangelical church protests against a new constitution approved in February 2019, and the government’s rejection of attempts by several denominational leaders to register the Alliance of Cuban Evangelical Churches.

Suárez has also covered another taboo topic: The Military Units of Aid to the Production (UMAP), euphemistic name for concentration camps to which the government, from 1965 to 1968, sent those considered a “social scourge.” Among them were artists, homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, priests, pastors and lay evangelicals.

Suárez wrote about UMAP in an award-winning report that records pastor Alberto González describing how he was subject to more than 12 hours of work, torture and humiliation for being a student of a Baptist theological seminary.

Recently the independent Diario de Cuba published Suárez’s extensive article on violations of religious freedom in Cuba, particularly harassment and detention of leaders of the Apostolic Movement, one of the most punished members of the Body of Christ on the island.

In the most recent of his books, “The Breath of the Devil: Violence and Gangsterism in Cuba,” Suárez shares the account of gang members who have converted to Christianity.

“Cuban officials say that this doesn’t exist, that there are no gangs,” Suárez said.

Suárez has also reported for Newsweek and Univisión, along with Christian news sites Evangélico Digital and Evangelical Focus. Regularly targeted by authorities as a result of his work, in 2016 Suárez was expelled from the Latin American Press Agency, Cuba’s official state news agency.

Prior Summons

On Feb. 5, DSE officials summoned Suárez and his mother to a police station in Havana.

A captain identified only as Enrique interrogated him for three hours, threatening that his family would suffer “consequences” if he continued reporting outside state controls, Suárez said. The official also informed him of an indefinite restriction on travel outside the country.

Cuba’s list of people put under such travel bans has grown to more than 200 Cubans, including 15 religious leaders, according to a list updated by Patmos Institute. The government typically imposes the ban on freedom of movement to citizens who communicate through unofficial channels. Suárez published his findings on this topic.

State security agents “are very upset when data is offered,” he told Morning Star News, “because it is not an opinion, and thus increases the credibility of journalistic work.”

The last three summons Suárez has received from state security officers have come as authorities demand social distancing to prevent further spread of the novel coronavirus. Critics on social media have lamented that authorities don’t care if those summoned for questioning become infected or die from the pandemic.

Previously, on Aug. 9, 2019, joint forces of State Security and the National Revolutionary Police arrested Suárez in Guantánamo while he was on his way to conduct an interview, according to Evangelical Focus. At the provincial headquarters of the Ministry of the Interior, he was interrogated and threatened with prison if he ever returned to the city.

Officials filed a report of alleged counterrevolutionary activity, and he was handcuffed and deported from the city of Guantánamo.

Suárez had intended to interview members of the Rigal-Expósito family and journalist, lawyer and Catholic Roberto Jesús Quiñones, who also ended up in jail for trying to defend the pastoral couple’s efforts. In late March Pastor Expósito received a commute to serve the rest of her sentence at home. Her husband remains in prison.

Shortly after the trip to Guantánamo, Suárez and six other Christians, along with artists and intellectuals, addressed an open letter to the Cuban government demanding freedom of for pastors Rigal and Expósito, freedom of expression, press and movement and opening of the Cuban educational model that is under strict state control.

On Sept. 14, 2019, upon arrival at José Martí Airport from Spain, Suárez’s passport was taken by immigration officers, according to the Havana-based Association for Freedom of the Press. They led him to an office within the terminal, where a Political Police (DSE) officer who identified himself as Danilo questioned him about the event he attended. Suárez later received back his passport.

Since then authorities have been increasingly antagonistic toward him, culminating in the April 3 summoning of him and his mother. In that interrogation, he said, the official told him he was “putting on a shirt that was too big for him,” and that his attitude “typifies the crime of mercenaryism.”

Become a Christian News Network Supporter...